As mentioned in Part 1 of this series, the NCAA 2016 Convention wasn’t a total loss. A major piece of legislation was approved in concussion protocols (long overdue in my view) that require school medical personnel (not a team doctor) to approve a return to playing field.

But another set of significant recommendations, alleviating some of the time demands on student-athletes, was deferred until January 2017. Yes, the “time demands” legislative proposals were not discussed publicly in depth, were not voted upon substantively and were essentially, for all practical purposes, not considered sufficiently well-thought through to be ready for adoption. “Next year” was and is the party line. I must say it is hard to believe that all these smart people, including university presidents, could not come up with a suitable solution.

Basically, this NCAA 20-Hour Rule is intended to insure that student-athletes have enough time to spend on academic and campus activities – beyond the time they spend on their chosen sport. But, the reported data demonstrate that students across the Divisions are spending way more time than 20 hours both in and out of season on athletics. To be sure, some of the reason is that athletes want to spend time of their sport to be both fit and competitive. But, it is not just the “fault” of students.

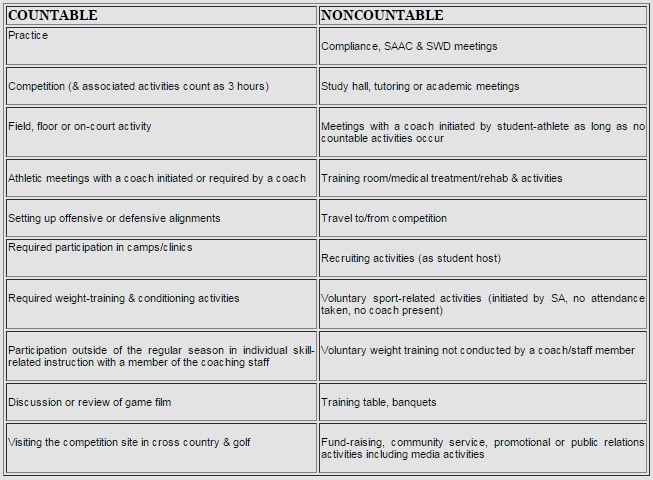

Another part of the problem is how the 20 hours are actually calculated. There are detailed charts showcasing what does/does not count, and here are several examples, selected to demonstrate how the rule fails to provide quality time measures. According to the NCAA, competitions (and all related activity including travel) are designated to count for 3 hours, regardless of how much time is actually spent. Consider this: for teams with conference sites that are a goodly distance away from their campuses, the competition days can be long and sometimes over-night stays are needed, including for bad weather. Three hours is a ridiculously low, artificially set number.

A table of countable versus non-countable activities (via Notre Dame Compliance)

A table of countable versus non-countable activities (via Notre Dame Compliance)

Add to this that time in the training room (a necessity to stay healthy and heal) does not count toward the 20 Hour Rule; neither do non-coach supervised individual workouts and weight training. Students call these “captain” monitored work-outs “moptionals,” an apt term.

I appreciate that this is not a simple problem. Balancing priorities is tough and calls for hard choices and compromise (something at which we are far from good). But, here’s the really troubling part. Student-athletes have asked for and want more free time away from their sport. They actually want to be part of the college community and spend time both in the classroom and socializing. They want time to visit their families. The student voices on this issue are not equivocal. Just look at the study results, one of which was conducted by the NCAA.

Consider, too, the student-athlete reaction to the decision at the NCAA 2016 Convention to postpone action on the 20 Hour Rule: they were angry and thought their interests were not being taken into account. They are not wrong and some coaches agree that the 20 Hour Rule does not make sense.

This issue is made thornier by the fact that many students need to work significant hours to be able to pay for college (and extras), an issue particularly for non-scholarship athletes in DIII but with implications for DI and DII students who are under partial scholarships or need added revenue for social activities, travel home and sundries.

There are two competing threads at work here that need to be separated and then addressed. Some student-athletes did not want the just passed stringent concussion protocols; they wanted to keep playing even if there were known serious long-term health risks. To be sure, some athletes are leaving their sports to protect their health. But, the reason for the newly enacted rule is, in essence, to protect students from themselves (and students tend to have short time lines) and from overzealous coaches and team physicians and outside doctors chosen by an injured player. Perhaps parents too.

There is an element of paternalism in the concussion protocol context – and the research demonstrates it is justified. So, in this instance, the student voices have been and now are overshadowed by science and the best medical thinking.

In the context of the 20 Hour Rule, students are speaking up and out and in this instance, their coaches, institutions, many of the Conferences and the NCAA are not listening or if listening, they are not acting quickly enough. The reasons for pursuing paternalistic approaches do not work here as they did with the concussion rules. The time spent outside athletics is not a life/death issue, and the students themselves want the different and “protective” result – a loosening of their obligations.

In this instance, there is research too and it supports the students’ position pointing out that the collegiate experience is diminished because they do not have enough time off from athletic pursuits. Somehow, because this research goes pro-student, it is not as powerful.

Now, the President of the NCAA took two quite remarkable stands in his speech at the 2016 Convention (and I have not been easy on the NCAA as many readers know): he applauded and even encouraged the recent student protests (that included protests by athletes), giving credence to student voice; he also observed that the time-away issues needed to be addressed to restore balance between athletics and academics. In a nutshell, on the latter point, President Emmert was trying to restore meaning to the term “student athlete.” Bravo.

So, why are student voices not being heard now with respect to time off and what are the real issues lurking beneath the surface?

First, I suspect everyone knows that the 20 Hour Rule currently in effect is honored in the breach. If you want to win at the highest level, 20 hours is not enough. So, winning is what is driving the proverbial train – and with winning comes recruits, money, prestige, acclaim, high coach salaries, donations, school spirit. And, to be fair, if you want truly exceptional results, there is no shortcut to being athletically ready. Time and talent are, generally speaking, the currency that enables winning.

Second, I think we have isolated athletes and athletics from the balance of the campus life of a student. The result is that the need for a more well-rounded experience is not universally shared by AD’s and coaches, among others. If things are to change in this regard, there needs to be real pushing from folks in positions of power; students’ pushing is not enough apparently. Ironically, protests might work – as occurred at Mizzou, albeit for a different issue.

And, not to be cynical, but even if it is mandated that athletes have two days off a week or fewer hours, would that actually work in the real world and culture of collegiate sports? I’m not so sure. Whatever new guidelines are put in place, folks will be trying to develop “legal” work-arounds. Finding the loopholes will likely be someone’s task within an athletic department.

Third, if we really want to live by the ideal of the student-athlete, we need to do a way better job of messaging and role modeling what that means. And, if that ideal is passé and has to fall by the wayside, then we need to say that and change the options for how we handle student-athletes on America’s campuses. Pretending doesn’t work; students see through that. And rules honored in the breach proffer a bad example for sure.

Here’s an idea, given the seeming current paralysis of the NCAA and the Athletic Conferences. Why not have some campuses voluntarily work to help their athletics by reducing their schedules and giving them an extra day off? Yes, take action – a type of protest that seems to fall within President Emmert’s approval zone. Maybe that will cause more athletic losses; that’s possible. But, the opposite is possible too – happier, more well-rested and well-rounded athletes who are proud to represent their institutions while “experiencing” college in the best sense. There could mean athletic success and improved recruiting.

I hope one of the campuses among the Big Five Conference schools might just be willing to try. Yes, it would be brave. It would also be the right thing to do for their students – the very people we are charged to serve within higher education.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.